The Academy of Architecture has invited activist-designer Selçuk Balamir to be Artist in Residence for the 2021-2022 academic year. The Winter/Summer School was held from June 30 till July 8, in the summer of 2022.

Selçuk Balamir is a designer, educator and activist, working on postcapitalist politics, commoning practices and climate justice campaigns. He co-founded grassroots disobedient action collectives (codeROOD, Fossil Free Culture, Queers4Climate) and co-developed the creative and strategic framework of Climate Games (peer-to-peer disobedience platform) and Shell Must Fall (mass disruption of shareholder meetings). He co-initiated the social housing projects NieuwLand (postcapitalist urban commune) and de Nieuwe Meent (cooperative based on commoning). His PhD in Cultural Analysis from University of Amsterdam is on postcapitalist design. He teaches New Earth (eco-social design) at Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam.

The Winter Summer School consisted of two parts: the Training Weekend, intended as a crash-course on key concepts and principles of Climate Justice, was hosted by social movement organisers. All photos from the training are on Flickr.

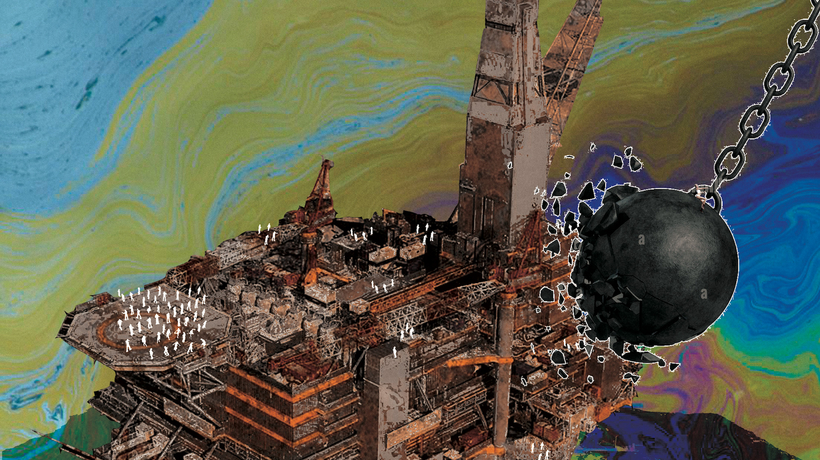

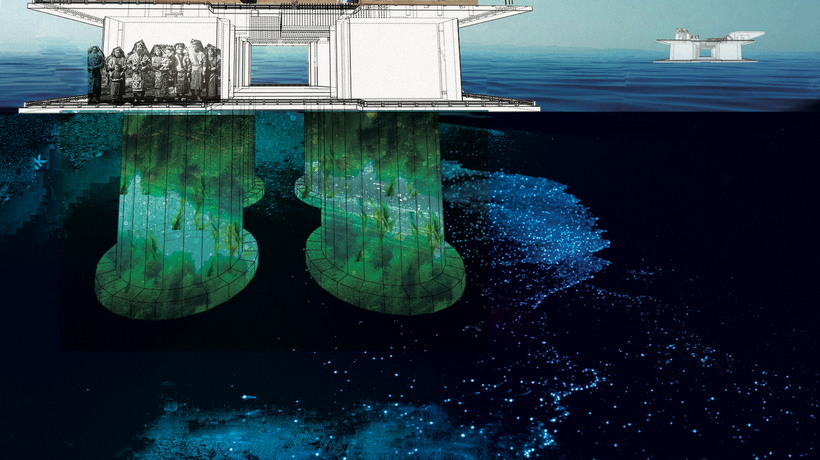

The second part were the Assignment Days where students collaborated on a spatial design project with an explicit just transition agenda. Each team was assigned an infrastructure site of (Royal Dutch) Shell, and they were asked to imagine and design a rapid, responsible and justice-based scenario for decommissioning and repurposing that piece of Shell’s legacy. Each day, the students fast-forwarded ten years and produced an image and a caption encapsulating the successive stages of the transition. They were supported by professionals, researchers, and educators in the design and sustainability fields.

The final results were presented at the former Shell Lab canteen (now the cultural centre Tolhuistuin). The students were asked to roleplay their future selves and to recollect what each site has speculatively gone through in the form of storytelling. The performative finale closed with a discussion held by the four respondents who reflected on the students’ work. Photos from the performative finale are on Flickr.

The outcomes are published as a wall calendar spanning four decades (2020-2060), intended as a daily reminder of this generation's task. The calendar was exhibited at We Are Warming Up festival on 26-30 October 2022. Alongside 80 original images and edited captions, the publication also contains the introduction lecture transcript and a reflection piece on the process. To appraise the evolution of a site over each decade, please fast-forward twenty pages.

Images below: Eastern Petrochemicals Complex, Singapore 2020-2050; by Kevin Groothuis, Sara Tamer Shalaby, Rick Wolters, Edoardo Seconi and Patrick van Schaik. Sakhalin–2, Sea of Okhotsk 2020-20250; by Jurgi Cínta Egaña, Tim Arends, Yorick van Eetvelde and Hannah Liem.

Prior to the Winter Summer School, David Keuning spoke about Balamir’s plans and expectations in regard to his collaboration with spatial designers, the decolonial critique of ecomodernism and the relation between ecological transition and social justice. You can check out a preview below, and read the full interview at the Annual Newspaper 2021-2022! (direct PDF download link):

The summer school opens with my introductory lecture entitled From the Shell of the Old, intended to stir up the debate on the ethical-political role of designers in a just ecosocial transition. The following two days are led by eight brilliant women, all of them inspiring grassroots movement leaders based in the Netherlands, who facilitate four workshops to introduce the key concepts and methods of Climate Justice. During these workshops, the students experiment with social movement tools, engage in debates to develop their position, and get to know their group members. These groups are then assigned a piece of Shell infrastructure (such as offices, labs, refineries, pipelines, oil rigs or gas stations), for which they are asked to imagine a rapid, responsible and justice-based decommissioning and repurposing scenario over the next decades. Instead of proposing a singular designerly gesture that is frozen in time, each assignment day is intended to fast-forward five years, capturing various stages of the transition. In this process, the students are supported by design experts and knowledge holders in sustainability. The Summer School culminates in a performative finale that takes place in the former Shell office canteen, where the groups present their work in the form of storytelling from the future. We also intend to compile the results in a ‘Decade Zero’ wall calendar, as a daily reminder that transition is inevitable, but justice is not. Only our intentional collective efforts can make that happen.

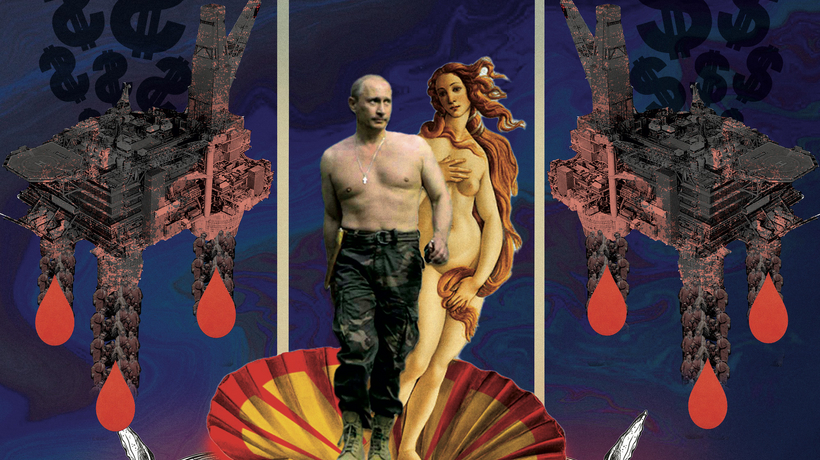

There are several reasons to focus squarely on the company formerly known as Royal Dutch Shell. As complex and widespread as overdeveloped societies’ entanglement with carbon pollution may be, there is absolutely no doubt about the paramount role, responsibility and culpability of the fossil fuel industry. A handful of companies have dominated the energy sector and profited from fossil fuels and their derivatives. They have built corporate empires with geopolitical, infrastructural, financial and ideological underpinnings. They knew about the consequences of their actions for decades and doubled down on this path. They have manufactured dangerous distractions like greenwashing, ‘carbon footprint’ and ‘carbon offsetting’ to divert attention and deny their part. Besides, the recent Milieudefensie court case victory against Shell has made clear that the company is to be held responsible for the emissions of their customers. Now, Shell is certainly not alone, and all Carbon Majors are equally to blame. After all, Shell is not an exceptionally evil company, but the problem is structural; any privately-owned, publicly-traded energy company is going to maximize fossil fuel extraction to maximize profits for their shareholders. So indeed, any carbon-intensive sectors upstream or downstream that are organized as capitalist enterprises are part of the problem.

That said, I believe there is merit in focusing on a concrete case study instead of talking about an abstract ‘energy transition’. Also consider that Shell, with its colonial history and intimate ties with the Dutch state, still benefits from social acceptance and national pride in the Netherlands. This is an obstacle to debating the kind of energy transition we are going for: do we want green capitalist monopolies on renewables or a decommodified, cooperative energy democracy? This is why the Summer School takes the comprehensive decommissioning of Shell as a non-negotiable, inevitable starting point for imagining the just transition, as well as a Dutch-specific case study on taking responsibility for colonial and ecological reparations.